MANILA, Philippines – In the coastal town of Alburquerque, Bohol, a centuries-old tradition continues to simmer slowly but surely — both figuratively and literally. This cultural ritual is how the asin tibuok, or “unbroken salt,” is made.

As Bohol’s renowned artisanal pride, it is considered one of the rarest salts in the world. With origins tracing back to pre-Hispanic times, it’s a multi-generational craft that only a few families in the country still know how to do.

Not many people are privy to this process, but thankfully, as a way to shine a light on this important facet of Filipino culture and Boholano identity, groups are now allowing guests to witness the painstaking yet persevering craft behind the coveted “salt of the earth.”

At the newly opened South Palms Spa and Resort in Panglao, tourists can see the “dinosaur egg salt” take shape from start to finish. The experience is part of the resort’s “M Moment” program by MGallery — with “M” standing for meaningful and memorable.

What was once used as a form of currency is now a landmark of culture and artisanal heritage. “People used it to trade for food; that’s how important it was to our food culture,” our M Moment guide Krai said.

“But unfortunately, because of modernization, we’re slowly starting to forget many parts of our history and past,” she said. “That’s why we’re here — to reconnect with ingredients that are beginning to be forgotten, and to highlight them in the most fascinating and meaningful way.”

Man with a mission

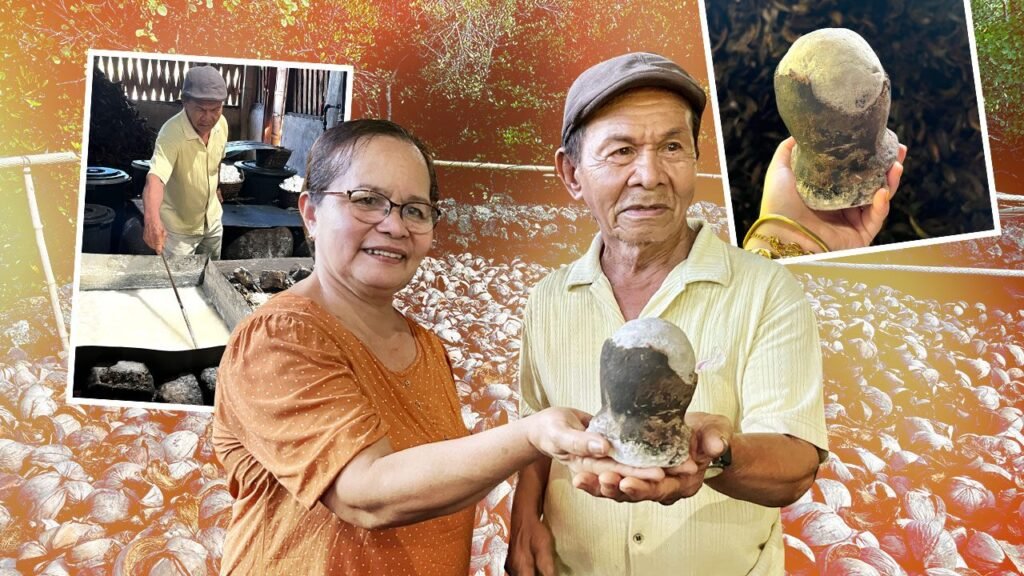

Tan Inong Manufacturing is one of the last family-owned producers in the town dedicated to preserving this craft. Led by Tatay Nestor, who learned the process from his grandfather at the age of seven, the family has been hand-making asin tibuok for decades, alongside his sister.

The art was almost lost; but his brother, Father Chris, who is based in Australia, was key in helping to revive the practice. The business was at risk of stopping because of many challenges — the rise of cheap, commercial salt, typhoons, earthquakes, and even the pandemic. But Father Chris insisted on reviving it, not for money, but out of respect for their ancestors.

It’s a tedious art that Tatay Nestor, who is in his late 70s, leads; but the many steps involved have already been imparted to his family members.

It all begins with the collection of coconut husks. These husks are soaked in seawater for several months in specially dug pits, allowing them to absorb minerals from the sea.

After soaking, the husks (called daob) are burned daily until they turn to ash. This slow-burning process, done over several days, produces a fine mixture of ash called gasang, the key filtering medium for seawater and what helps give asin tibuok its smoky, slightly sweet taste.

At the site we visited, a vast lot of burnt coconuts lay drying under the sun, waiting to be chopped. Chopping itself takes a full day of manual labor, turning the husks into smaller pieces. Once chopped, the husks are carried indoors and stacked into small mountains, ready for the next step.

While this is happening, Tatay Nestor’s other family members mold the clay pots by hand, small earthenware pots that are later on heated in a furnace to hold the dome of salt.

Next, seawater is poured through layers of coconut husk ash — this is the main filtration system. The water passes through this ash repeatedly, in filters that are located on top of the deck. Seawater is filtered through ash in three stages, collected, and used after three months of soaking, chopping, drying, and filtration.

This creates a concentrated brine, rich with absorbed minerals.

Every step undergoes quality control — it can’t just be regular seawater. It has to be the perfect salinity. They use a “tanchameter,” a small branch from a specific mangrove tree. Thrown into the saltwater, if it floats, the salinity is perfect. If it sinks, it’s no good.

Once ready, the concentrated brine is carefully collected and poured into the large clay pots, little by little. The pots are placed over a fire fueled by coconut husks and cooked slowly for up to eight hours, sometimes longer, depending on the water’s salinity. It is bubbling actively, until it solidifies into its distinct, egg-like form.

As the liquid evaporates, salt crystals begin to form, hardening into a solid mass inside the pot. Eventually, the salt expands and cracks the pot, revealing a dome-shaped block sometimes likened to a “dinosaur egg.”

Krai also explained that Iloilo has its own version of asin, which also uses coconut. But for Bohol, asin tibuok uses coconut husks. The problem is, if salinity keeps getting lower, asin tibuok will fail. This salt requires ideal salinity to solidify properly.

“The quality and time of asin tibuok depends on the water’s salinity,” Krai explained. “If the salinity is good, they can finish earlier. But if it rains, or when water levels rise, the salinity drops, and cooking takes much longer. Sometimes it lasts until late in the afternoon, around 4 or 5 pm.”

That’s why the process is so elaborate and tedious; it requires three days of cooking, eight hours each day. “You can’t just collect seawater, boil it, and expect asin tibuok to form. If you do that, you’ll only end up with powdered salt, not the signature dome shape,” she said.

Communities also fear the effects of global warming and climate change; when it rains, salinity drops. When ice melts, salinity drops. And if that continues, it affects the salt-making process.

It’s a beautifully complex and time-consuming art that takes a minimum of three months to finish; often more, depending on factors like the seawater, the multi-stage burning, and the slow cooking. It truly is a labor of love; one production cycle produces only 210 asin tibuok pots. Each asin tibuok sells for P800.

Not just a ‘trend’ — it’s a sacred ritual

It isn’t just labor for Tatay Nestor’s family; asin tibuok-making is also spiritual. “For the first three hours of cooking, nobody is allowed near the fire except the master salt-maker and one trusted helper,” Krai said. “No jewelry is allowed, nothing artificial on the body. Everything must be natural. This has been the practice since the 1800s, and they’ve kept it until today.”

This is also why tourists from South Palms are not allowed to “insert” themselves in the asin tibuok-making process; interactive activities are not encouraged (only the clay pot molding can be tried out). Guests can observe and even converse with the salt makers up close, but not offer a helping hand. This also helps to protect the sacredness of the tradition, and not put it at risk of commercialization.

“We don’t want to disrupt the process,” Krai said.

South Palms doesn’t earn from the tours either; instead, the initiative functions as a form of CSR (corporate social responsibility) — proceeds go back to the community and help keep the tradition alive.

“That’s why we’re here — because we were given the opportunity to reconnect with ingredients that are starting to be forgotten, and to highlight them in the most fascinating way. We want to be progressive in how we present them because we’d like to shine a light on this little world.”

For now, asin tibuok’s future is both as vital and fragile as the salt itself. Aside from climate change risks, the art is not being adopted by younger generations as often as before.

Krai shared that when she asks Boholanos what they know about asin tibuok, many can barely explain it. The demand for the product remains minimal — and yet, there are signs of hope.

“Fortunately, asin tibuok is gaining recognition again. It’s FDA-approved and even exported to the United States,” Krai said. It’s also growing into a hot commodity in fine dining restaurants in Manila, with both local and international chefs utilizing the salt in dishes, drinks, and desserts; and as a famed item sold at artisanal food fairs around the country.

Slowly, the food and beverage industry is starting to bring the asin tibuok’s magic to shores beyond Bohol.

“This is something we should be proud of. This is Boholano culture. This is tradition,” Krai said.

And as we shine a light on these cultural practices, hardworking Filipinos like Tatay Nestor are able to pass down a piece of their heart to the generations to come — while we, in turn, get to enjoy the beauty of what the Philippines has to offer on our plates. – Rappler.com