This First Person article is the experience of Marie Pascual, who lives in Toronto. For more information about CBC’s First Person stories, please see the FAQ.

Hot platters landed hard on tables near us and steam rose as diners reached in to take generous helpings. It was my 26th birthday and I’d chosen Congee Queen — the kind of place my parents would’ve picked. No fuss. No menus. Just food.

My friends seemed a bit lost when the waiter came to our table. Wanting my friends — a mix of immigrants and international students who had made Toronto home — to feel that same comfort I felt at this restaurant, I did what my mom always did. I ordered for the table.

Black pepper squid, beef with noodles, Super Bowl congee, turnip cakes, seafood vermicelli. The waiter gave me a small grin.

“Is that everything?” he asked, teasing.

I laughed awkwardly and nodded, a little embarrassed. As he walked away, the table burst into laughter.

It was the kind of laugh that said, “There she goes again.”

I’d done this before — taken charge of the ordering, played host even when it wasn’t my house.

But this time, something about it made me pause.

It struck me then how instinctual my urge to share was. When I was 14 my mom handed me the menu at a restaurant and said, “You know what we like.”

It felt like she was passing me the matriarch’s baton.

Ordering for everyone was not just a habit. It was how I made sure no one felt overlooked.

Back in the Philippines, my family used to live in poverty and mealtime looked very different. It started long before the dinner table out by the sea. My grandparents would fish, the kids hauled in the catch and the women would set up the dining room while the men cooked. My parents told me the idea of sitting in a restaurant and being served by strangers was almost unimaginable.

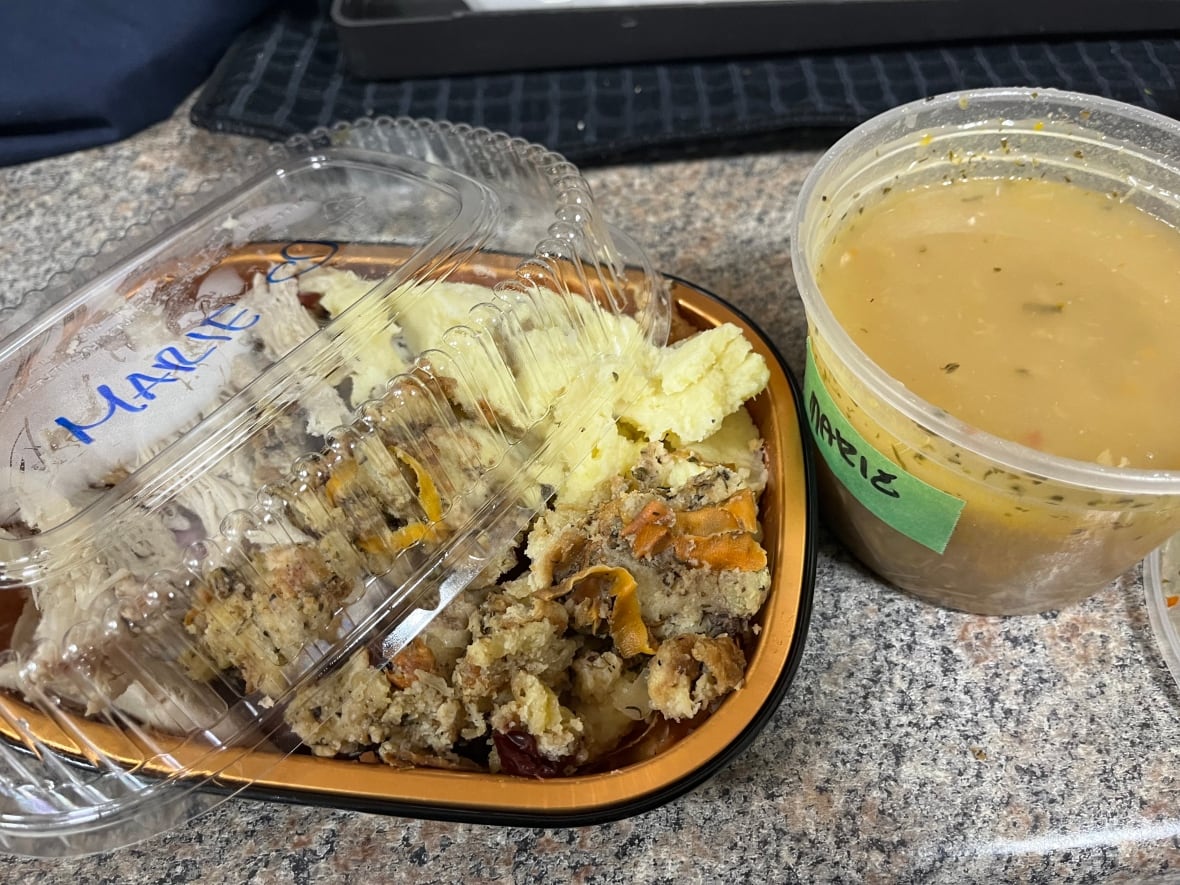

I was born in Canada and raised by Filipino parents who brought those customs with them. They taught me to value communal meals. If you had food, you shared it. No one ever left your table still hungry. Even now, when I visit my parents, my mom makes enough adobo to feed a small army and packs containers for me and my partner to take home before we have even asked.

But outside our family, that kind of care sometimes misses the mark.

I have offered samples of my food to friends or co-workers, only to realize no one else at the table did the same. It left me feeling awkward, and even a little ashamed, like maybe I was too much.

In my culture, I learned through visits to the Philippines from relatives and stories passed around the table that it was almost embarrassing not to have leftovers. Clean plates could look like you hadn’t made enough.

No one ever asked, “Are you sure you want to share?” It was a given.

Meals were meant to spill over, onto every plate, across the table, through the hours. Extra rice. Extra spoons. The promise that there would always be enough for anyone who walked through the door.

If you did not send people home with baon (little take-home bundles), guests would quietly think you were kuripot (stingy) and too careful with your abundance. Generosity was not just a virtue. It was a kind of social insurance. Better to have too much and share than look like you had not cared enough to prepare.

When I moved into my own place to be closer to work, I realized something was missing every time I opened the fridge. Not just food, but the chaos. My tita‘s cassava cake in recycled margarine tubs. My mom’s 1970s macaroni salad — sweet, mayo-heavy and always topped with shredded cheese — that made me wish I was at her table. Or when I didn’t see my dad’s coffee mug sitting on the table from morning until night, the emptiness of my home felt loud.

That’s not to say I don’t see the merit in the more individual way of ordering food. It is simpler, it respects allergies and food preferences, and sometimes it is just easier not to negotiate with differing food choices or personalities.

One night after work, I sat down with co-workers and ordered a deep-fried soft-shell crab sandwich just for myself. No one asked to share, no one looked confused. I was raised to think that putting yourself first was selfish, even shameful. But in that quiet moment, it felt like I was finally learning how to take up space. Not just at restaurants, but in life.

Practicing individualism, even in something like ordering meals, still feels uncomfortable for me — yet also strangely freeing. I’m not sure I can always do this. Maybe that is my small rebellion against the polite distances we keep, my way of making sure no one leaves still hungry or carrying a hunger they cannot quite name. Maybe I will always order too much — but I won’t be too much. I’ll be just me.

Do you have a compelling personal story that can bring understanding or help others? We want to hear from you. Here’s more info on how to pitch to us.