Everyone’s story begins somewhere.

For CityNews reporter Joanne Roberts, that somewhere is Winnipeg’s old Mother Tuckers Restaurant.

It’s where her mom and dad, two young adults from Quezon City and Manila, met while working after having immigrated with their families from the Philippines.

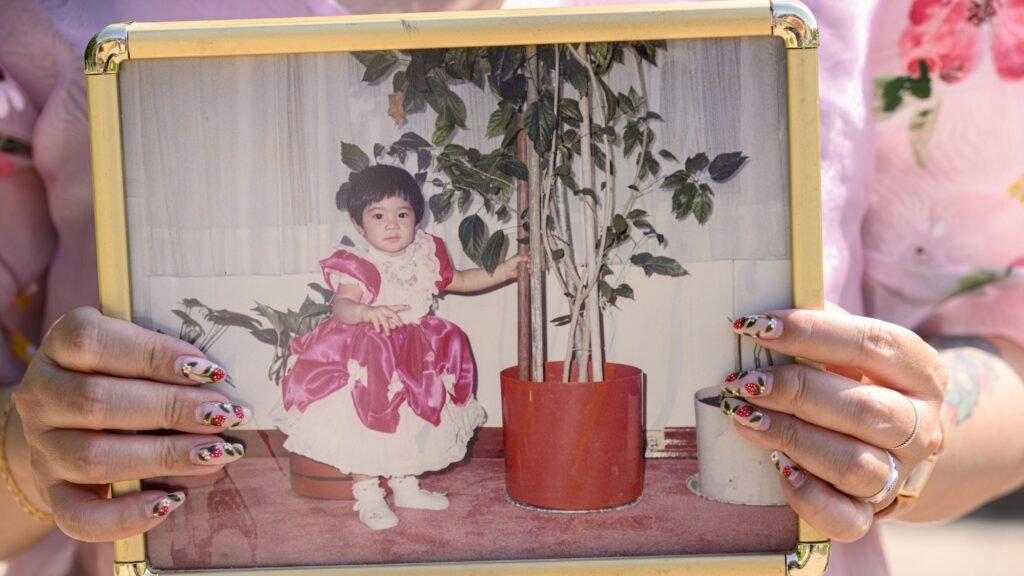

That led to them starting a family of their own – giving birth to a daughter who years later, now feels she never really learned about her Filipino side. Torn between her Canadian last name (Roberts) and her “true” Filipino maiden name (Fabro) — a product of western naming practices sometimes erasing cultural background — between where she’s born and where her parents are from, she feels like she only knows half of herself.

That feeling is what prompted this journey to trace the threads through history, legacy, healing – and everything in between – in hopes of finding a piece of her identity that’s been missing for a long time.

And it all begins with meeting historian Jon Malek in Winnipeg’s garment district: the “birthplace of the Filipino community.”

Jon Malek: For a while, this was the garment district where so much of the Filipino community started, where some of the first trailblazing women came. All started here.

Joanne Roberts: Wow. So, how do you know all of this?

Jon: Well, I first heard about the garment district from community members. There’s a lot of history work done within the community, and they’ve done a lot of oral histories. And because the garment district was active in the ’60s, ’70s and ’80s, many of them are still alive and their children are still alive. And, you know, as I heard these stories, I start looking around.

This is what a historian does. You hear about something, and you go looking for it. You go in the archives. A lot of information I got was in Canada’s first Filipino newspaper published in Winnipeg, the Silangan, which had a lot of info about the garment district. And a lot of the stories I get come from the people who have lived here, worked here for a while.

This area was Philippines, in Canada. Not far from here along Notre Dame was a little stretch that was called Filipino Town. A lot of garment workers, mostly all women, would live in apartments around here, usually four or five to a room. And on their days off, they’d either go to church or they’d go down to Eaton’s to window shop. So the stories are out there.

Joanne: So do you think if I was born, say, a generation earlier, there would have been a really good chance I would have ended up working at one of these factories?

Jon: Probably not. It tended to be a pathway for newcomers. So the first wave was in 1968, October, when the first wave of Filipino garment workers came from the Philippines. But it was really popular in the ’70s and in the ’80s.

And the deal was, the company would pay your airfare, would arrange for you to have an apartment, would make sure you could integrate. And as long as you worked for them for two years, all of that would be paid off, and you would get your permanent residency. So women could come here and work in somewhat challenging conditions.

But within a matter of years, start to bring their families over. So the community we see today, it’s very diverse, but so much of it is touched by the garment industry. So you probably wouldn’t have ended up in it. But if you had come here in the early ’80s, throughout the ’70s, that probably would have been a very, very likely pathway.

Joanne: So my parents came here separately. My dad’s family is from Manila. My mom’s family is from Quezon City, but I don’t actually know too much about their immigration journeys. So what was it like for a lot of people?

Jon: You know, different generations have different questions, right? So your people in your position, you have that question, you know, how did we end up here.

And so there’s a lot of youth that I’m finding, Filipino youth, finding that out for themselves. So students taking on research projects to find out, what was it about the Philippines in the ’70s that led my parents to leave?

And for those parents it’s hard to say. Coming from the ’70s, coming from the ’80s, this is the height of the garment industry recruitment. But Canada is also, this is the height of the multicultural era.

The points system, which is something that we also need to remember. Before 1967, immigration from the Philippines was actually barred, except on an ad hoc basis. There were laws that said people of Asian descent, were not permitted to immigrate to Canada unless there were very specific circumstances.

Joanne: Wow. Okay.

Jon: Yeah. So the previous wave to to Canada and to Winnipeg, particularly where health professionals or doctors, nurses, health technicians coming up from the United States, and this happened from 1959, throughout the ’60s and until 1967, each immigrant was an ad hoc, basis by the minister of education.

So when the the first wave of garment workers recruited to Winnipeg came in October 1968, this was one of the tests of the new immigration system. And one of the things that alarmed government officials is what numbers they would be dealing with. So Canada, prior to that, was concerned about keeping a certain character of Canadian society.

And so when we get into the 1960s and ’70s and ’80s, changes are also happening in the Philippines, economic changes, social changes, political changes. And this is what’s sort of driving people to look for opportunities abroad. Now, without knowing specifically about your parents, they probably had some skill, some labour skill that Canada saw and said, we would like that labour. Because that’s exactly what happened with the garment workers is that the women knew how to work machines.

Not just sew, but to how to work the modern sewing machines and how to work in an industrial, factory. And another thing to understand too, is that in the Philippines, Filipinos, because of centuries of colonialism, are familiar with Western culture and values and society. But they also speak English very well.

Joanne: And can we talk about just the landing here? I hear stories from friends all the time that now when we immigrate there are supports in place. But that wasn’t necessarily true back then.

Jon: Well it depends. Some of the stories I’ve heard from garment workers is that if you were recruited by a company in the Philippines, they would arrange your airfare, they would arrange for your first few nights in a hotel, and then they would arrange for you to have an apartment.

So when you landed, you had everything ready to go. Some started work the next day. So in those cases, I’ve heard stories of Filipinos landing in the airport and there’s 100, 200 Filipinos waiting to greet them.

Maybe not Filipinos they know. But as you know, that doesn’t matter. But if you were in a different stream and then maybe this is, this is relevant to your parents where they come on their own, they’re the first one in the family.

And then it could be a far more lonely experience.

Joanne: Okay, I can’t help but notice that we are right near one of my favorite places in Winnipeg, Toad Hall Toys. Would this have been part of the garment industry?

Jon: There’s various information that says both 70 Arthur and 54 Arthur, and I’ve come to learn that it’s actually one building.

Joanne: I actually know the people who are here at Toad Hall. Do you think we can… Let’s go in and see what happens?

Joanne: Hi, I’m Joanne. This is Jon. We were walking around, and we actually heard that town hall used to be part of the garment district. Do you know anything about that?

Dianne Thompson: I do!

Joanne: Oh my goodness. Can we talk about it?

Dianne: Sure. Let’s have a chat.

Joanne: Sure.

Dianne: The tin ceilings would have been here for sure when it was a garment factory. And the floor is still original, so that would have been here then. I’ve been told that when Toad Hall took over the space and renovated this space, that there was still, like the floors are wooden and they were picking out by hand little needles and little bits of snaps and stuff from in between the cracks of the wood.

Joanne: Do you think that it’s possible that underneath these floors, there’s still there’s still snaps and needles just sort of sealed underneath there.

Dianne: Without a doubt. Yeah, I’m sure there are.

Joanne: So before we got here to like this space in the store, I did hear some chatter from the front. Just sort of about what pick-up times were like from the women who worked here. Can you tell me about that.

Dianne: Like when Toad Hall was here and the garment factory was still here because they did overlap, that a lot of the women would get picked up from the factory by their husbands or boyfriends who were really into car culture. And so lots of really cool cars would come and pick up their wives and girlfriends.

Joanne: Yeah, some things don’t change.

Jon: Nope. They stay the same.

Joanne: I think it’s really cool. Just sort of how full circle this specific place has come for me. My very first mentioning of Toad Hall was my elementary school teacher who had bought a puppet here. And then she would sing songs with us with this puppet. And she told me it was Toad Hall. And then so finally I came here for the first time as a teenager, and just fell in love with it and obviously still come here. I still do stories here. Now, hearing from you that this is part of Filipinos’ history here in Winnipeg, that’s like…

Jon: It’s funny how it’s coming back to your youth.

Joanne: Yeah, definitely. And I’m thinking about, you know, all of the pins and needles and all that that’s still underneath the floor.

Jon: And you know, those Filipino youth looking for their background, even when you’re adults, it’s looking for that childhood, right? That childhood knowing where you come from, knowing what it means. And for those born in Canada — they’re from Canada and born in Canada — but that Filipino heritage, it’s there. It’s in the floorboards.

Joanne: Yeah. And thanks so much for sharing it with me. I’ve been looking for this second half of me that’s not totally Canadian. Not totally Filipino. I think every time I come here now is going to feel very different.

Jon: And it just tells us that that identity like you said, both Canadian, both Filipino, it means different things for different people. So there’s no right answer for you to find it. It’s whatever you find is what the answer is.

Joanne: Shall we head back outside?

Jon: Let’s go.

Joanne: So the entire point of me asking you to come down and doing this special is, so my last name is officially Roberts. but my maiden name is Fabro. But neither of them have really quite felt like mine. I don’t know why. And I was wondering, just as you have observed the Filipino community and its history, how important are names in our culture?

Jon: Well, you know what? One thing I’ll start with is the naming practice when someone gets married. So when a woman marries, in European society, you usually drop your maiden name and pick up the last name of your spouse.

As a young woman in the Philippines, in Filipino culture, your middle name is actually not your middle name. It’s your mother’s maiden name. And your last name is your father’s last name. When you marry, you take your father’s last name as your middle name. And then you take on your spouse’s name.

So in that naming system, which some do and some do not practice here in Canada, there is that holding on to that past. But I always found it interesting that single women would maintain their mother’s maiden name. But in terms of what names we have, there is so many traditions wrapped up in Filipino culture.

So your names could be coming from any number of backgrounds. So a lot of them are Spanish.

A lot of them are our traditional Filipino names, meaning, pre-Christian.

So obviously your name, whether it’s your given name or your received name or your family name, it can mean a lot. And in the diaspora, so especially in Canada, names are becoming different. So you’re saying Roberts, which might not so be associated with Filipino names.

My wife’s name is Malek. Because we’ve married, she’s taken my name. But it differs from people to people.

Like, let’s think about this for a minute. We’re in the heart of where so many families of Filipinos in Canada started. But tell me, what do you see that’s Filipino?

WATCH: CityNews Connect: A Filipino Heart in Canada

Joanne: Not much.

Jon: No. So when you’re a Filipino living in Canada, and especially if you’re coming from that generation, you can not feel rooted. You can feel like this doesn’t belong to you.

Because when you look, what you’re looking at is 19th century, early 20th century colonial architecture. What we’re seeing is a story of land lost to Indigenous people. It does not physically represent the story of Filipino garment workers. We have to go inside and we have to look in the floorboards for those pins.

So language is a form of representation. So when you think about the fact in the last few years, we’ve had Manila Street. I just found out the other day there’s a Luzon Bay. These are acts of Filipinos, petitioning their governments to acknowledge their presence. And it is big. It is very big to have these little spaces.

But when you’re in the Philippines, it’s all around you. The street names, the statues, the buildings that represent your history. Your ancestral house, where your family came from in Manila or Quezon City, the streets, you can go there and see where they grew up, and you can feel a sort of affinity to it.

Joanne: So, you were recently in the Philippines.

Jon: Yes. Like last week.

Joanne: How was it over there?

Jon: Beautiful. It’s always beautiful. I’ve been there many times. It’s just a great place to go. The Philippines is a society, is a culture deeply aware of its identity and history. They’re very much aware of important figures. And especially when you’re, when you’re in Manila, the areas I was staying around. You know, there are statues of past figures. But what’s interesting is that you have both the colonial and independence era.

Yeah. So in Rizal Park, which is sort of like the national park, you have a big statue of Lapu Lapu. That colourful being one of the first heroes of the Philippines known for his violent episode with Magellan. But then, not far from him, you’ll see a statue of Jose Rizal, the national hero of the Philippines, the first one to reuse the term Filipino to mean the Indigenous population.

And then not far from that, you have a statue of Legaspi, who was the first Spanish governor in this in the 16th century. Yeah. And all of this just coexists as part of Filipino history, Filipino identity.

Joanne: Thank you so much for meeting me here in time for everything. I don’t even know what to say. I think that, you know, starting this journey and looking for a part of my identity that feels like it’s been missing. Feels like this is a great start. Thank you so much.

Jon: Yeah. Thanks for showing me.

This was the first installment in a three-part CityNews Connect series exploring Filipino identity in Canada.