In many headlines and on social media, the term “evangelical” is often conflated with “conservative,” “white,” “male,” and “American.” Many in the U.S. evangelical community are resisting that conflation, actively pushing for a new vision for evangelicalism that situates it within a global landscape. For these evangelicals, the future of evangelicalism is less James Dobson and more Botrus Mansour.

As such, Christianity Today often uplifts the multicultural face of global evangelicalism, suggesting that decentering the white American experience offers a new path forward for evangelicalism. Hence, the oft spoken refrain: The new face of Christianity is not a white man, but a woman in Africa.

But as someone shaped by the evangelical movement in the Philippines, I want to offer a necessary complication. While evangelicalism is growing across the world, I find it hard to believe that global evangelicalism holds the key to redeeming evangelicalism. The reason for my disbelief is that global evangelicalism continues to rehearse the same forms of right-wing politics that we are seeing expand in the U.S.

Case in point: right-wing evangelicalism in the Philippines. When strongman Rodrigo Duterte ascended to the presidency in 2016, he quickly launched an authoritarian “War on Drugs” that claimed the lives of 30,000 urban poor. Filipina scholar Neferti X. M. Tadiar argues that this “war” functioned to clear urban spaces of the poor, making them more attractive to foreign investors. In this regard, Duterte’s “tough-on-crime” persona sought to present the Philippines as a safe and lucrative destination for investors. This image was built at the expense of the urban poor, who were criminalized and disposed of through the militarization of the police force and the incentivization of vigilantes.

As journalist Hannah Keziah Agustin noted for Christianity Today, some Filipino evangelicals regarded him as “the best” president of their lifetime. Duterte’s recent arrest by the ICC for crimes against humanity was cause for lament for these evangelicals. Some Filipino evangelicals believed Duterte’s administration offered hope for a better and safer country. As one Duterte supporter put it: “People aren’t used to rulers with an iron fist. But when [Duterte] became mayor and president, he cleaned everything up, and drug addicts were scared.”

What concerns me about that statement is the striking similarity between evangelical Duterte supporters and evangelical Trump supporters, both of whom share the notion that a strongman persona is necessary to “clean the streets” and make the country “safer.” For his part, President Donald Trump has argued that his mass deportation agenda, which is putting the U.S. on track for one of the “deadliest years in immigration detention,” is making the country safe again.

While the Philippines is predominantly Roman Catholic, with evangelicals comprising only 3% of the population, this does not necessarily translate to a lack of political prominence. In recent decades, Philippine evangelicalism has gained traction in the public sphere in large part due to the influence of American white evangelicalism—seen both in the influx of U.S. evangelical corporate presence in the country and in the rise of evangelical politicians seeking to bring policies similar to Trump’s into Philippine politics.

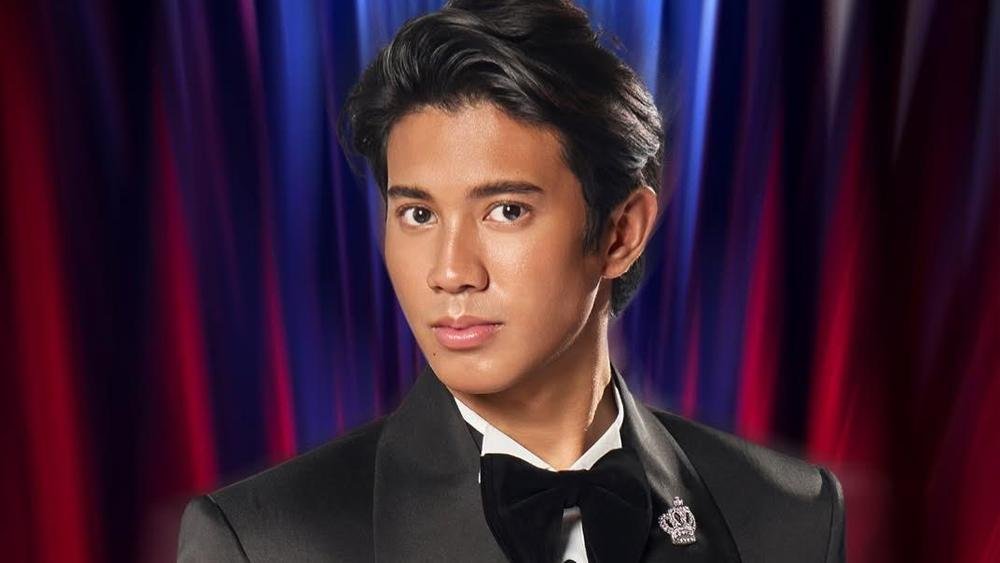

For instance, prominent evangelical leader Eddie Villanueva has lauded Trump’s anti-LGBTQ+ platform as a model for “the global community to uphold values rooted in God’s Word.” Villanueva is not only the founding pastor of Jesus Is Lord Worldwide—a Philippine-based megachurch with more than 5 million members—but also a politician actively campaigning for a stronger right-wing turn in Philippine politics, often pointing to Trump’s authoritarian takeover of the U.S. as a model for Filipinos to embrace. On his podcast, Villanueva urges listeners in Tagalog to pray for Trump: “[T]he best thing that we need to do as children of God is to pray that Trump’s actions would be victorious for the good of everyone.” (My translation.)

Another area of alignment between white evangelicals and Filipino evangelicals is support for Israel’s violent campaign in Gaza. This support is fueled by the Philippine Council of Evangelical Churches and the Christian Broadcasting Network’s regional arm, which hosts countrywide events and television programs for Filipino evangelicals. Both organizations receive funding from U.S. evangelical institutions, calling on Filipino evangelicals to “give thanks,” “pray for,” and “stand with” Israel.

Indeed, these political practices closely mirror those of white American evangelicalism and are not limited to the Philippines. In many African countries, for instance, journalists and scholars have traced the curtailment of queer rights to U.S. evangelical missionaries and organizations. There is also the sobering rise of the far-right in Brazil, propelled by Brazilian evangelicals. As ethicist David Gushee argues in Defending Democracy from Its Christian Enemies, which examines the global landscape of Christians supporting anti-democratic practices, evangelicalism must reckon with its role not merely as a passive embracer of anti-Democratic governance, but as an active participant in creating “authoritarian reactionary Christianity.” evangelicalism must confront the fact that it has not only been complicit but actively breeds “authoritarian reactionary Christianity.”

READ: Meet the Born-Again Christian Who Brought Down Namibia’s Sodomy Laws

Again, I find it hard to believe U.S. evangelical outlets and leaders who claim that, by taking a turn toward “multiculturalism” and “global” evangelicalism, they are challenging Trump and the MAGA movement’s hold over evangelicalism. For instance, the late pastor Tim Keller wrote for The New Yorker that the future of evangelicalism lies in a younger, multiethnic, and globally shaped movement that resists the rigid “package deals” of U.S. partisanship—including Trump-aligned politics—while holding fast to historic evangelical theology.

As ethicist Isaac Sharp shows in The Other Evangelicals, discussions of evangelical “diversity” in recent years have emerged among white never-Trump evangelicals largely to save face, while lacking the critical self-awareness to recognize that their version of evangelicalism—as structurally and historically white, colonial, male-dominated, and capitalist—has long “pushed out” non-white, female, queer, and more progressive or leftist evangelicals. Similarly, author Amar Peterman noted in 2024 that this vision “reflects a Christian imagination” that excludes certain evangelicals from its purview, an exclusion that continues to marginalize many.

For instance, while Christianity Today seeks to present itself as a moral voice against “evangelical” Trump supporters, it continues to platform stories promoting anti-LGBTQ+ sentiment and authors who deny that a genocide is taking place in Gaza under international law. If Christianity Today can be seen as representative of a multicultural and global evangelicalism that is the future of Christianity, it is clear that they envision a very particular form of “global evangelicalism” that fails to challenge the white-dominant and non-affirming politics at its core.

Is there any possibility for a reconstituted evangelicalism beyond the constrictions of dominant conservative voices? Can global evangelicalism truly offer an alternative to the dominance of white evangelicalism in the U.S.?

Is there any possibility for a reconstituted evangelicalism beyond the constrictions of dominant conservative voices? Can global evangelicalism truly offer an alternative to the dominance of white evangelicalism in the U.S.?

My answer is no, unless it is willing to engage in serious structural critique.

Notions of “global evangelicalism” that ignore the long, structural histories of colonialism, patriarchy, queer- and trans-phobia, and militarism will not liberate but will instead remain complicit in the same systems of violence. If evangelicalism is to have any future, both in the U.S. and elsewhere, it must take the necessary step of turning away from its complicity in structures of violence. Only then can evangelicalism be the proclamation of the good news that Jesus Christ has come to restore all creation from sin and death, and that all people are invited to participate in his salvific work.

It is also equally necessary to assess which voices in global evangelicalism are being highlighted. If Filipino pastor-politicians like Villanueva or the anti-Palestinian programming of the Christian Broadcasting Network in the Philippines continue to represent the face of global evangelicalism, then evangelicalism will remain in the same cycles of structural violence and injustice. There are other evangelicals we need to be paying attention to who persist outside of mainstream evangelicalism, or, as Sharp contends, are “pushed out” of the dominant narrative.

If evangelicalism has a future, then it will be with the progressive and leftist evangelicals, queer and trans evangelicals, anti-imperialist and pro-Palestinian evangelicals, all of whom are challenging the dominant narratives that have overwhelmingly determined what it means to be an evangelical.

While I am not convinced by the version of global evangelicalism that dominant evangelicals espouse, I do still hope that evangelicalism can be practiced in a way that is truly life-giving for all people, without exclusion. In order for that to happen—to re-orient our moral imaginations away from the grasp of conservatism and right-wing politics that have conflated being “evangelical” with being white, queer-antagonistic, trans-antagonistic, and anti-Palestinian—evangelicalism must do more than superficially diversify itself or appeal to tired identity politics. It must confront the systems that hold us all captive and strive for the liberated world that God calls us to pursue.

Evangelicalism must become a movement defined not by the oppressors, but by solidarity with the oppressed. That is my hope for its future. And—borrowing from Sharp—it is the othered evangelicals, those cast out by the dominant evangelicals, who are already leading the way.