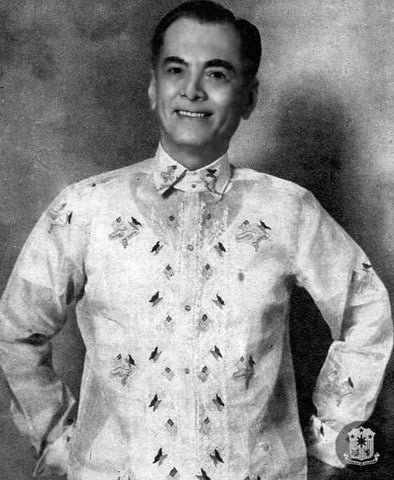

President Manuel L. Quezon, the “Father of the National Language,” is pictured here in his iconic barong Tagalog, a symbol of his commitment to Filipino identity. As the architect of the national language, his efforts to unify the diverse linguistic landscape of the Philippines continue to influence the nation’s cultural identity today. His legacy lives on every August through Buwan ng Wika, a celebration of the Filipino language and the values of unity and national pride. (Photo Credit: National Historical Commission of the Philippines )

When the architects of the Philippine Republic debated the foundations of nationhood, one question loomed large: how could a fragmented archipelago, divided by hundreds of tongues, stand as one nation?

For Manuel L. Quezon and the framers of the 1935 Constitution, the answer lay in the creation of a wikang pambansa, a national language that would serve as a bridge across regions.

In 1936, Quezon established the National Language Institute to determine which native language could best serve as the basis of this unifying tongue.

By 1937, the Institute recommended Tagalog, citing its rich literary tradition, widespread use, and central location. The decision was not without controversy, but Quezon declared Tagalog as the foundation of the national language, seeing it as both a symbol of independence from colonial rule and a practical step toward unifying the people.

The institutional celebration of the national language began a decade later. In 1946, President Sergio Osmeña proclaimed March 27 to April 2 as Linggo ng Wika to honor the birth anniversary of Francisco Balagtas, the great Tagalog poet. In 1954, President Ramon Magsaysay moved the celebration to August 13–19 to coincide with the birthday of President Quezon on August 19. Finally, in 1997, President Fidel V. Ramos signed Proclamation No. 1041, expanding the observance into a full Buwan ng Wika, celebrated every August.

This history shows that Buwan ng Wika was never just about costumes or contests. It was meant to embody a vision: that language could be the cement of a fractured republic and the soul of a free nation.

Yet the national language project has always carried tension. Critics argue that elevating Tagalog to “Filipino” marginalized other languages such as Cebuano and Ilocano, leaving many feeling excluded from the very idea of national identity.

Some scholars describe it as a form of linguistic imperialism, where one region’s tongue overshadows the others.

There are also questions of practicality: in an economy and academic world dominated by English, is Filipino an obstacle to global competitiveness?

Advocates counter that Filipino was never meant to be a frozen Tagalog. By design, it is dynamic and evolving, enriched by other Philippine languages and even foreign borrowings. Far from being exclusionary, its adaptability makes it stronger. For advocates, Filipino is not simply a tool of communication but an assertion of dignity, independence, and self-definition in a globalized world.

This debate between inclusivity and exclusion, between pride and practicality, explains why Buwan ng Wika remains relevant today. It is not a month for nostalgia but for reflection. What does it mean to have a national language in the 21st century? Is it merely symbolic, or is it still essential to nationhood?

The framers of the Constitution were practical. They believed a shared language could unify an archipelago divided by geography and history.

In modern times, practicality takes on a different form. Filipino and English coexist in schools and workplaces, while regional languages remain anchors of identity in the provinces. To push one at the expense of the others risks division. To let Filipino shrink into ceremonial use would be to abandon a central pillar of statehood.

For the global Filipino diaspora, Buwan ng Wika carries a different weight. It is not only a reminder of home but also a bridge across generations and continents.

For children of immigrants who risk losing touch with their roots, the national language becomes a lifeline of identity.

For overseas workers, it is solidarity, a code of belonging in faraway lands. In an age where borders blur but identity can be fragile, Filipino remains a compass.

Buwan ng Wika reminds the diaspora that even as they thrive abroad, their words carry the rhythm of home.

The way forward is balance. Filipino must be nurtured as the common language of unity. English must be used as a tool for global engagement. Regional languages must be preserved as treasures of cultural heritage. Only then can Buwan ng Wika move beyond ritual into real nation-building.

Language was the bet of the framers of the Constitution. It is still our wager today. If we let Filipino fade into a once-a-year ritual, we lose more than words – we lose a part of who we are.