This article is part of the Placemaking Project, an ongoing effort to uncover, collect and share Asian American histories in Evanston. Learn more about the project here. Research is ongoing and more articles will follow. Please contact Melissa Raman Molitor, Placemaking Project founder and founding director, Evanston ASPA, if you would like to learn more or get involved with the project: evanstonASPA@gmail.com

Introduction

The end of the Spanish-American War can be seen as “a defining moment in U.S. and world history, one that has affected hundreds of millions of lives in large parts of the globe.”[3]

As a result of the Spanish-American War in 1898, Spain ceded the Philippines, its long-held colony, along with its colonies of Puerto Rico and Guam, to the United States. Spain also relinquished its claims to Cuba, which formally gained its independence, but came largely under U.S. control. The United States paid Spain $20 million in order to take control of the Philippines. The country then became a U.S. territory.[4]

Thus began four decades of American control of the Philippines and the beginning of the first substantial phase of Filipino immigration to the U.S. In this first phase, from 1900 to 1946, the majority of Filipino immigrants who came to the U.S. — 96% — were single men.[5]

Recruited to work on farms and sugar fields, most Filipino immigrants settled in Hawaii and California. Filipino immigration to Evanston and the Chicagoland area, although on a smaller scale than on the West Coast, also began in the early 20th century and the number of new arrivals would increase dramatically well into the 1920s.

By the mid-1920s, Chicago was home to the largest number of the state’s Filipino immigrants; roughly 1,000 Filipinos lived in the city, mainly concentrated on the Near West Side.[6]

By 1933, a total of 2,011 Filipinos were living in Illinois – the third-largest population of Filipino immigrants in the country.[7]

In Evanston, scores of Filipino men and a few women came to the city in the first four decades of the 20th century; their experiences in Evanston — and in the U.S. in general — were shaped and also limited by the particular impact of colonialization.[8] For decades, they were both part of the U.S. but also held at a distance.

As we identify and research early Filipino immigrants for the Placemaking Project, we are working to restore their biographies to the larger historical record. Doing so provides a fuller and more accurate picture of the city’s history and the many people who have lived and worked in Evanston; their contributions are significant. This partial history traces some of the stories surrounding early immigrants from the Philippines. It is by no means complete. This is a history in progress.[9]

Pensionados

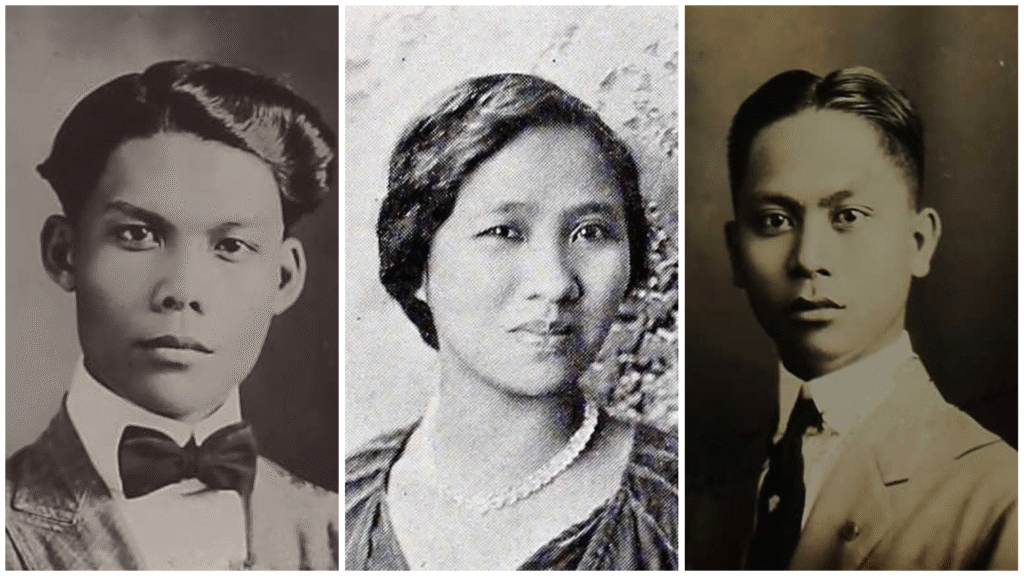

In 1906, 19-year-old Timoteo Abaya (1887-?) arrived in Evanston and enrolled at Northwestern University. Abaya is the first known recorded Filipino resident of Evanston. He was the first of many young, primarily male, Filipino citizens who came to the United States to seek higher education in the first half of the 20th century.

“[W]e give Mr. Abaya our warmest greetings,” wrote the Daily Northwestern in welcoming him to the university, “as one who is a foster brother under the fatherland; As one whom we are rejoiced to receive into the family of our alma mater.”[10]

Born in Pagsanjan, Laguna, the Philippines, Abaya was 16 years old when he arrived in the United States in November 1903.[11] He came with the first group of 100 young Filipino men who were recipients of competitive academic scholarships offered to Filipino residents by the U.S. government. Abaya and the others were given $500 per year to come to the U.S. to study at schools across the country.[12] Known as pensionados, the students, who ranged in age from 16 to 20, studied a wide variety of subjects, from law and medicine to commerce and journalism.[13] In total, roughly 500 students came to the U.S. under the pensionado program.[14]

American government officials developed the pensionado program in an effort to cultivate loyalty among Filipino citizens. One of the program’s goals, stated William Alexander Sutherland, the first superintendent of Filipino students in the U.S., was to ensure the “complete Americanization” of the young students.[15] The first group of pensionados were required to pledge that they would return to the Philippines once they earned their degrees. Then, it was planned, they would help “Americanize” the U.S. territory.

While the pensionado program would evolve over the years it was in effect (1903-1943), the first group of students — which was also the largest — came from elite families. Timoteo Abaya would be followed by many other Filipino students, both pensionados and also so-called “self-supporting” students who lived in Evanston in the 1910s to1940s.

After they arrived in the U.S., Abaya and the other pensionados were assigned to schools in Southern California before heading to colder regions of the U.S., including Evanston.[16] Abaya and another pensionado attended Santa Paula High School in Santa Paula, California.

After their first year in California, the students headed off to various schools across the U.S. Abaya would soon be on his way to Dixon, Illinois. He was one of 42 pensionados sent to schools in Illinois in 1906 — the highest number of students assigned to a single state.[17]

Before reaching Illinois, however, there was just one stop to make.

Abaya and the other pensionados were taken to St. Louis where the Louisiana Purchase Exposition, also known as the St. Louis World’s Fair, was underway. There, they remained for a month working as “guides and as waiters in the mess hall.”[18] It was a humbling and damaging experience for the young men. For, the fair was notorious for its racist presentation of Filipino culture which included a “living display” of 1,200 Filipino people who had been brought to the fair from the Philippines.[19]

U.S. secretary of war and future U.S. president, William Howard Taft, who had served as civil governor of the Philippines in 1902, conceived of the idea for the display.[20] The fair’s overwhelming presentation of the residents of America’s new territory was that of an “uncultured” and “uncivilized” people — a dehumanizing characterization that would linger for decades.

Aside from working at the fair, the pensionados were presented as the “best representatives” of Filipino culture, having been chosen for the scholarship program due to their high degree of refinement and sophistication. It was clear that these young men would do more than pursue an education in the U.S. They would also be expected to serve as ambassadors, representing the Philippines to a broad American audience.

At the end of the fair, along with other pensionados, Abaya was awarded a “Medal of Honor with Diploma” which read:

“The government of the Philippine Islands with the approval of the Secretary of War confers upon Timoteo Abaya a Medal of Honor of the 5th class as recommended by the Superior Jury of the Philippine International Jury for services in furthering the welfare and progress of the Philippine islands.”[22]

After the fair, in the fall of 1904, Abaya attended Dixon Business College and then DeKalb Normal (Northern Illinois University).[23] After completing his course of study, he arrived in Evanston sometime in 1906. It is not known where Abaya lived while in Evanston. The pensionados were assigned to live with families in private homes and their addresses are difficult to determine.[24]

In September 1906, two of the very few female pensionados, Eleanor de Leon and Isabel Florendo, came to Evanston where they were entertained by sisters Ethel, Florence and Louise Frost at their home at 641 Hinman Ave. The luncheon table was decorated with “place cards of Philipino [sic] flags and a profusion of flowers.”[25] All the guests were classmates at Saint Mary’s College in Notre Dame, Indiana.

A month earlier, de Leon and Florendo attended a reunion of pensionado students at Gross Point Park hosted by the Rev. Edward J. Vattmann (1840-1919), a resident of Wilmette and a U.S. Army chaplain who had served in the Philippines. At the time, Vattmann was in charge of 128 pensionado students studying in the Midwest; he had also accompanied the pensionados to the World’s Fair.[26]

At the reunion picnic hosted by Vattmann, more than 30 pensionados, representing 14 Midwestern schools, were present. Abaya was likely among the picnic-goers.

At the picnic, Vattmann praised the students for their hard work and clean living and the “happy throng” enjoyed a day of “merrymaking” which included dancing in the park pavilion.[27]

After the picnic, Abaya began classes at Northwestern University. He was said to “profess a keen interest in the student life here and in his school work.”[30] He was active in campus clubs. In December 1906, for example, he gave a lecture about Christmas customs in the Philippines at a meeting of Northwestern’s Spanish Club.[31]

In May 1907, he took part in the annual satirical “Trig play.” His character was a “mascot” named “Awata Gahoma” — a derogatory name, particularly since the role was performed by a student who came from a territory outside the U.S.[32] The name also reflected a common tendency among Americans to project feelings of homesickness on the pensionados.

The pensionados were categorized as “American Nationals.” (As were all Filipino citizens.) They were, on the one hand, “at home” and welcome in the U.S. For, as a result of the U.S. control of the Philippines, Filipino citizens were able to apply for U.S. passports and travel freely to the U.S.

They were also bound to their host country: As a part of their U.S. passport application, they were required to sign an oath of allegiance to the United States and submit sworn statements that they did “not acknowledge allegiance to any other government.”

On the other hand, Filipino immigrants were also held at a distance. Pensionados were often referred to as “wards” or, as the Daily Northwestern had referred to Abaya, “foster brothers.” One Chicago journal described them as “lonesome strangers in a very strange land.”[35]

Not only did Filipino immigrants in the U.S. face discrimination (particularly on the West Coast, where their numbers were far higher than in the Midwest), but they would also, with some exceptions explained below, be barred from attaining U.S. citizenship until 1946.[36]

While the Northwestern University community extended a public welcome to Abaya, and the university, it was noted, showed “an especially generous spirit toward the newcomers,”[37] it was clear that American perceptions of Filipino people and culture were often tinged with paternalism and racism. And, for many American citizens, the question of whether or not the Philippines should ever be granted its independence was shaped by the same kind of racist views that many held at the time: that the Filipino people as a whole were uncultured and unevolved — unable to “govern” themselves — a perception that had been on view in the 1904 World’s Fair display.

Years earlier, in August 1899, during the Philippine-American War, a sign for the U.S. Anti-Imperialist League (which opposed the U.S. annexation of the Philippines or any other territory) was posted at the corner of Chicago Avenue and Davis Street in Evanston. The Evanston Index questioned whether such a sign was “traitorous.”[38]

Indeed, the sign’s appearance did not seem to reflect the general position of Evanston’s leadership class which publicly supported both the U.S. annexation of the Philippines and the U.S. military presence in the Philippines. (Roughly 90 Evanston residents served in the Spanish-American War, while many others served in the Philippine-American War.[39]) “The Philippines were taken by necessity,” as Evanston Mayor Thomas Bates said.[40]

Soon, the material “benefits” of the new American territory were on view in Evanston. From food to fashion, references to exported Filipino culture began to appear in the Evanston papers. (A daily menu suggestion published in a 1925 issue of the Evanston News-Index, for example, included “Filipino roast.”)

Around Evanston, lectures and events focused on Filipino politics, culture and history were now regularly hosted. In 1907, for example, the Women’s Missionary Society of the First Presbyterian Church hosted a stereopticon lecture titled “Our Filipino Cousins.”[42]

In 1911, the Field Museum in Chicago opened a major exhibit of items from the Philippines that had been collected by anthropologists Fay-Cooper Cole (1881-1961) and his wife, Mabel Cook Cole (1880-1977). The Coles, who lived at 2343 Ridge Ave. in Evanston in the 1920s, had deep ties to the city. Both were 1903 Northwestern University graduates.

Fay-Cooper Cole frequently gave lectures in Evanston, including a talk titled “Wild Tribes of the Philippines,” which he presented at various Evanston locations over the years, including St. Luke’s Church and the Woman’s Club of Evanston.[43]

As more pensionados arrived in Evanston over the years, they would follow in Timoteo Abaya’s footsteps and give lectures on “customs and life in the Philippines.”[45] “Remember at all times,” the U.S. government instructed Filipino students, “that you are representing the Filipino people and that thousands of Americans will judge the whole Filipino race by the way you live.”[46]

As the pensionados served as ambassadors of Filipino culture in the U.S., many worked to correct the distortions perpetrated by the colonizers and many would also make the case for establishing an independent Philippines.

Especially for the first pensionados, the challenge of being part of a system of education intended to “Americanize” them, while still deeply connected to the culture of their home country, placed them in a difficult position. Their roles in the U.S., as many saw it, were twofold: to band together, as so many immigrant groups often do, and provide support to one another, while also venturing out, immersing themselves in their new surroundings and becoming part of the fabric of America.

Working for ‘Harmony and Equality‘

In the Midwest, Filipino immigrants were less frequently subject to racially motivated harassment or attack as they were on the West Coast. Still, one of the most publicized instances of violence directed at Filipinos took place in Evanston.

In April 1919, Rodolfo Manolo and Marcelo Plattao, two Filipino students at the Armour Institute (now the Illinois Institute of Technology), were assaulted and robbed of $185 and a gold watch at Maple Avenue and Foster Street in Evanston. They had been escorting home Marie McDonough and Rose Nichols, two Evanston telephone operators.[47] Their assailants: “a trio of enlisted men consisting of two sailors and a soldier.” The students were “battered up as a result of the fracas.” They went to the Evanston police station, where Manalo made a statement: “I am a citizen of one of the colonies of the United States and I demand that I be given protection,” he said.[48]

The need for protection would spur the creation of a variety of informal support networks and social clubs, as well as formal organizations. In 1914, the Filipino Association of Chicago was founded by a group of workers and students, including Northwestern University students.

Incorporated in the state of Illinois in 1917, the association would grow to be one of the largest of its kind in the country. Its first motto, “Harmony and Equality,” represented the members’ efforts “to promote a brotherly relation among ourselves; to offer aid and protection to Filipinos that are in the United States; to advance the good behavior and social conduct of its members” while also working for “a fair and truthful exposition of the relation between the Philippines and the citizens of the United States.” One of the group’s stated aims was also to promote “a true friendship between Americans and Filipinos.”[49]

Other associations were organized, including one just for students: In June 1920, a group of students met at Lake Geneva, Wisconsin, to draft a constitution for the Filipino Students Federation of America. One of the group’s founders was Lucas Herrin, a student at Garrett Biblical Seminary (now the Garrett-Evangelical Theological Seminary) in Evanston. At the conference, the students gave unanimous approval to a resolution asking for “the granting of Philippine independence.”[51]

Students across the country also began to publish journals, recording their experiences in the U.S. and reflecting on Filipino and American culture and politics.

The earliest pensionados were required to return home after earning their degrees and help develop and “modernize” the Philippines.[53] Once back home, many would become highly successful in the fields of government, medicine, law, education and science. They would also inspire others, prompting more young people to come to the U.S. in search of education and opportunity. Among those so inspired was Carmen Aguinaldo-Melencio, daughter of Emilio Aguinaldo, erstwhile leader of the fight for Filipino independence and the first president of the Philippines.

Another female student from the Philippines who attracted national attention was Consuelo Marcos Valdez Fonacier (1900-?). In 1922, Fonacier arrived in Evanston. She enrolled at Northwestern University where she studied public speaking. A graduate of the School of Pharmacy at the University of the Philippines, she was not a pensionado but her education was funded by the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) in the Philippines. While in Evanston from 1922 to 1924, she lived at the Frances Willard “Rest Cottage,” headquarters of the American WCTU., at 1730 Chicago Ave.[54]

Evanston’s first known Filipino resident, Timoteo Abaya, was no exception to the rule of successful pensionados. After he earned a bachelor of science degree from Northwestern University in 1907, he returned to the Philippines.[56] A banquet was given in his honor, along with two other returning students, Firmo Borja, who had attended high school with Abaya in Santa Barbara, and José Valdez, a graduate of Notre Dame Law School who was later selected as delegate to the U.S. Congress representing the Philippines.[57] Abaya was soon appointed a “junior teacher” by the Bureau of Education and later served as the first Filipino principal of Pagsanjan Elementary School and academic supervisor of Laguna.[58]

The early pensionados who returned to the Philippines were sometimes disparaged for having become too “Americanized” in habit, speech, and outlook. But at the same time, the lure of American culture would continue to motivate others to venture to the United States, not only seeking higher education, but also economic opportunity. Many of this next wave of immigrants would not return to the Philippines. They would remain in the U.S., building a strong and growing community.

Next Up: Claiming a Place in Evanston’s History: Filipino Immigrants in Evanston, 1906-1946, Part II

About the author: Jenny Thompson, Ph.D., is a public historian and nonprofit consultant. You can email her by clicking here.

Author’s note: Many thanks to Kathy Alonso and Geronimo Cristobal for their significant contributions to this research. I am grateful to Northwestern University for permission to use images from the Northwestern Syllabus Yearbook.

[1] This article draws from a variety of sources that have been used to identify and research Filipino immigrants in Evanston. The main sources include: U.S. Census records; Evanston City Directories; journals and newspapers, including the Daily Northwestern, Evanston Index, Evanston Review, and Chicago Tribune; university publications, yearbooks, and catalogues; U.S. military service records; U.S. selective service records; U.S. passport applications; U.S. naturalization records; U.S. immigration records; birth and death records; and obituaries.

[2] Carolyn Im, “Facts about Filipinos in the U.S.,” Pew Research Center, May 1, 2025. https://www.pewresearch.org/race-and-ethnicity/fact-sheet/asian-americans-filipinos-in-the-u-s/ In the 16th century, the first known Filipinos arrived in what is now the U.S. The earliest Filipino settlement in the U.S. was the St. Malo community in Louisiana in 1763. Kirby Aráullo, “The First Asian American Settlement Was Established by Filipino Fishermen,” https://www.history.com/articles/first-asian-american-settlement-filipino-st-malo

[3] Baltazar Pinguel, “Reframing the Spanish-American War in the History Curriculum” in Debbie Wei and Rachel Kamel, eds., Resistance in Paradise: Rethinking 100 Years of U.S. Involvement in the Caribbean and the Pacific(Philadelphia, PA: American Friends Service Committee and the School District of Philadelphia, 1998), 12.

[4] Read more about the war’s impact and U.S. expansion at the time: “This Day in History, Dec. 10, 1898: Treaty of Paris,” Zinn Education Project, https://www.zinnedproject.org/news/tdih/treaty-of-paris/

[5] The word “immigrant” does not accurately describe all Filipino men and women who came to the U.S. in the first part of the 20th century since some intended to live in the U.S. temporarily. But for consistency, I use the word throughout this article to describe all Filipino people who came to the U.S. regardless of their intentions to remain or return to the Philippines. U.S. House of Representatives, Committee on Immigration and Naturalization, “Exclusion of Immigration from the Philippine Islands,” April 10, 1930, 4.

[6] Kimberly A. Alidio, Between Civilizing Mission And Ethnic Assimilation: Racial Discourse, U.S. Colonial Education And Filipino Ethnicity, 1901-1946. Dissertation. (University of Michigan, 2001), 140.

[7] In 1933, a total of 45, 208 Filipino immigrants lived in the U.S. On the mainland U.S., California had the largest number of Filipino immigrants (30,470), followed by Washington (3,480), Oregon (1,066), and New York (1,982). U.S. House of Representatives, Seventy-Second Congress, “Hearings Before the Committee on Immigration and Naturalization (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1933), 1-2.

[8] Many refer/referred to the Philippines as a (former) colony of the U.S. and the role the U.S. played in relation to the Philippines as colonization. While the Philippines was technically a U.S. territory, the relationship that developed between the two countries over nearly half a century was that of colonizer/colonized, shaped by unequal power. At the time of annexation, not all Americans supported it. In 1898, the American Anti-Imperialist League was formed in direct opposition to the U.S. annexation of the Philippines. Among its members were Mark Twain and Andrew Carnegie. See more: https://guides.loc.gov/world-of-1898/anti-imperialist-league.

[9] In many cases, these biographies are incomplete. For example, there are two records for Jennie Bracey, a Filipino woman who lived in Evanston, 1930-1931. Born in the Philippines c. 1875, she is recorded on the 1930 U.S. Census as a widow, working as a domestic worker for the Mincer family at 2707 Euclid. A year later, her name appears in the Evanston City directory. She is identified as working as a cook for the Evanston Community Hospital. Another incomplete biography is that of Julius (or Julio) Rios, another Filipino immigrant. In 1907, the Evanston Index reported that Julio Rios was under the charge of the Rev. Vattmann and working as a porter at the Greenwood Inn on Hinman Ave in Evanston. The 1909-1910 Evanston City directory lists Julius Rios as a porter at the Greenwood Inn. But beyond these pieces of information about Bracey or Rios, nothing more has yet been located. Research continues into these and other biographies and information will be added to the Placemaking Project website as it is uncovered. “On the North Shore,” Evanston Index, October 12, 1907.

[10] “Comes From Philippines,” Daily Northwestern, October 29, 1906.

[11] Passenger List, Steamer Korea, Pacific Mail Steamship Company, November 1903, California, U.S., Arriving Passenger and Crew Lists, 1882-1959, Ancestry.com

[12] “Education Report, 1905,” Report of the Commissioner of Education. Volume I. (Washington DC: Government Printing Office 1907), 359; Barbara M. Posadas and Roland L. Guyotte, “Unintentional Immigrants: Chicago’s Filipino Foreign Students Become Settlers, 1900-1941.” Journal of American Ethnic History, Vol. 9, No. 2 (Spring, 1990), 28.

[13] W. Reginald Wheeler, Henry H. King, Alexander B. Davidson, ed. The Foreign Student in America (New York: Association Press, 1925), 17.

[14] Adrianne Marie Francisco, From Subjects to Citizens: American Colonial Education and Philippine Nation-Making, 1900-1934 (Doctoral dissertation). University of California, Berkeley, 2015, 62. For more about the pensionado program see Geronimo Cristobal, “Gleaning from the Archives of the Pensionado Story,” 2021, https://scalar.usc.edu/works/gleaning-from-the-archives-of-the-pensionado-story/index.

[15] “Report of the Superintendent of Filipino Students in the United States Covering the Filipino Student Movement, from Its Inception to June 30, 1904,” in United States War Department, Bureau of Insular Affairs, Fifth Annual Report of the Philippine Commission, 1904 (Washington, DC: GPO), 1905.

[16] “Education Report, 1905,” Report of the Commissioner of Education. Vol. I. (Washington DC: Government Printing Office 1907), 358; Mario E. Orosa, “The Pensionado Story,” ND.

[17] Adrianne Marie Francisco, From Subjects to Citizens: American Colonial Education and Philippine Nation-Making, 1900-1934 (Doctoral dissertation). University of California, Berkeley, 2015, 66.

[18] Yen Le Espiritu, Filipino American Lives (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1995), 6.

[19] Learn more: https://asianamericanedu.org/1904-worlds-fair-exhibition-of-the-igorot-filipino-people.html

[20] Mark Bennett, ed. History of the Louisiana Purchase Exposition (St. Louis: Universal Exposition Publishing Company, 1905), 463.

[21] “Filipinos are Many at St. Louis Fair,” Evanston Press, August 27, 1904.

[22] “Report of the Philippine Exposition Board to the Louisiana Purchase Exposition and Official List of Awards Granted by the Philippine International Jury at the Philippine Government Exposition,” World’s Fair, St. Louis, MO, 1904, 73, 166.

[23] “Comes From Philippines,” Daily Northwestern, October 29, 1906.

[24] Yen Le Espiritu, Filipino American Lives (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1995), 7; Barbara M. Posadas and Roland L. Guyotte, “Unintentional Immigrants: Chicago’s Filipino Foreign Students Become Settlers, 1900-1941.” Journal of American Ethnic History, Vol. 9, No. 2 (Spring, 1990), 29; “Education Report, 1905,” Report of the Commissioner of Education. Volume I. (Washington DC: Government Printing Office 1907), 359.

[25] “Many Autumn Brides,” Evanston Index, September 8, 1906.

[26] “Rev. Vattmann’s Filipino Guests,” Evanston Index, August 25, 1906; “On the North Shore,” Evanston Index, October 12, 1907; “Chaplain Vattmann Retires,” Catholic Telegraph, June 12, 1913.

[27] “Rev. Vattmann’s Filipino Guests,” Evanston Index, August 25, 1906.

[28] “Rev. Vattmann’s Filipino Guests,” Evanston Index, August 25, 1906.

[29] “Rev. Vattmann’s Filipino Guests,” Evanston Index, August 25, 1906.

[30] “Comes From Philippines,” Daily Northwestern, October 29, 1906.

[31] Daily Northwestern, December 19, 1906.

[32] “Trig Cast Ready for Performance,” Daily Northwestern, May 24, 1907.

[33] “Trig Play,” Northwestern University, Syllabus yearbook, 1909, 194.

[34] In 1940, the Lewis Institute merged with the Armour Institute of Technology. Today the school is known as Illinois Institute of Technology.

[35] “ ‘Secret Society’ Found in Chicago,” Chicago Commerce, June 17, 1919, 12.

[36] Before 1946, U.S. military service was one means by which Filipino immigrants could attain U.S. citizenship. The first Filipino to become a naturalized U.S. citizen is largely believed to be Raymon Reyes Lala in 1898. But evidence suggests there may have been earlier instances of Filipino immigrants attaining U.S. citizenship. See more: https://uncommonwealth.virginiamemory.com/blog/2025/05/14/was-the-first-filipino-american-citizen-naturalized-in-norfolk-county/

[37] “On the North Shore,” Evanston Index, October 12, 1907.

[38] “Is it Traitorous?” Evanston Index, August 19, 1899.

[39] “A Notable Fourth of July,” Evanston Index, June 17, 1899; “For the Glorious Fourth,” Evanston Index, July 1, 1899.

[40] “Evanston’s Voice is Heard,” Evanston Index, May 13, 1899.

[41] Evanston News-Index, April 10, 1925; Evanston News-Index, July 14, 1923; Evanston Review, August 21, 1930.

[42] Evanston Index, April 6, 1907.

[43] Dorothy Palmer, “Social Activities and Personal Mention,” Evanston News-Index, November 15, 1915. Fay-Cooper Cole helped establish the University of Chicago’s graduate program in Anthropology. Mabel Cook Cole taught anthropology at Cornell University. She was the author of several books including Philippine Folk Tales (1916).

[44] Field Museum, Philippine Heritage Collection, https://philippines.fieldmuseum.org/heritage/narrative/4172

[45] Evanston News-Index, October 17, 1925.

[46] “What Filipino Students Coming to the United States Ought to Know,” (Washington, DC: GPO, 1921), 18.

[47] “Soldier and 2 Gobs Accused by Filipinos,” Chicago Tribune, April 7, 1919.

[48] “Filipinos are Robbed of $185 by Enlisted Men,” Evanston News-Index, April 7, 1919.

[49] Committee on Friendly Relations Among Foreign Students, “To the Filipino Students in the United States,” New York, January 1918, 14.

[50] “ ‘Secret Society’ Found in Chicago,” Chicago Commerce, June 17, 1919, 12.

[51] “Filipino Students Ask For Independence,” Philippine Herald (November 1921, Vol. 2), 5.

[52] Adrianne Marie Francisco, From Subjects to Citizens: American Colonial Education and Philippine Nation-Making, 1900-1934 (Doctoral dissertation). University of California, Berkeley, 2015, 72.

[53] Benito M. Vergara, Jr., “The Real Filipino People: Filipino Nationhood and Encounters with the Native Other,” in Dina C. Maramba and Rick Bonus, eds., The “Other” Students: Filipino Americans, Education, and Power (Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing, Inc.), 23.

[54] “Philippine Girl Vice Crusader,” Milwaukee Journal, January 11, 1924; “World Convention of W.C.T.U. Will Include All Nations,” Duluth News Tribune, October 29, 1922; “Consuelo Valdez Marries University Professor,” Leader Tribune, August 30, 1925.

[55] “Philippine Girl Vice Crusader,” Milwaukee Journal, January 11, 1924. Fonacier later taught at the department of Speech and Drama at the University of the Philippines.

[56] Northwestern University, Bulletin of Northwestern University, 1906-1907 (Evanston-Chicago: Northwestern University, 1907), 296.

[57] “Is Notre Dame Graduate,” South Bend Tribune, February 8, 1908; “The Teachers of Santa Cruz, Laguna,” Philippine Education, Vol IV, November 1907, 17.

[58] Bureau of Education Bureau of Civil Service, Government of the Philippine islands, Official Roster of Officers and Employees in the Civil Service of the Philippine Islands. July 1, 1914 (Manila: Bureau of Printing, 1914), 54; “The Teachers of Santa Cruz, Laguna,” Philippine Education, Vol IV, November 1907, 17; “Laguna,” Philippine Education magazine, July 1926, 102; “A Glimpse of the Past,” Francisco Benitez Memorial School, https://franciscobenitezes.wordpress.com/a-glimpse-of-the-past/ Research continues into Abaya. A located marriage contract reveals that by 1953 the 65-year-old Abaya was a widower. He married for a second time in 1953. “Marriage Contract,” City of Santa Cruz, Province of Laguna, December 23, 1953.

[59] “Chicago, ILL.,” The Philippine Republic, October-November 1925, 16. Fabella’s son, Armand V. Fabella, graduated from Harvard and became an influential economist and educator in the Philippines Roel Landingin, Public Choice The Life of Armand V. Fabella in Government and Education Anvil Publishing, 2017.

[60] Northwestern University, 65th Annual Commencement, June 19, 1923, 9. Mendoza returned to the Philippines and joined the faculty at the National University in Manila. Advertisement, The Tribune, June 18, 1936.