By Joel David

The reverberation of a life after one has died is no longer new because of the dissemination of media-generated popular culture. It should be no surprise that the departure of Nora Aunor has affirmed what film critic and Jefferson public service awardee Mauro Feria Tumbocon Jr. described as “a subgenre yet to be named, where Aunor plays herself as singer-performer” except that in the recently released Faney, she no longer exists in our world. The film, part of a substantial list of works already completed (some with her still alive in them), is evidence of how intensively she focused on the legacy she wanted to leave behind: not in terms of trophies or material wealth, but in the record of solid performances that she became known for since her emergence as the country’s most capable actor in the 1970s.

Faney also testifies to how carefully she cultivated artistic alliances, with Adolfo Alix Jr. taking the place of Mario O’Hara, whose untimely demise from leukemia she mourned openly. Alix was more prolific than O’Hara and already had a few noteworthy projects when he and Aunor first collaborated, but again like O’Hara, his growth trajectory found a grounding that it had been seeking out. Part of the confidence he needed was provided by Aunor herself, since her sheer presence in any type of undertaking always assured, at minimum, an exceptional delivery and a sense that she’d intervened in the project not for highlighting or glamorizing herself, but for enriching the text’s sociopolitical possibilities.

One byproduct of her renewed productivity, after an extended sabbatical in the U.S., lies in the number of industry participants who had been formerly indifferent, sometimes even hostile, toward her. Faney features a comic turn by Roderick Paulate in his famed Rhoda persona, playing a devotee who’s accused by another fanatic of betraying a rival star, with whom he erupts in a hair-pulling contest. The character who first mentions the film title is played by Althea Ablan, who’s typically millennial in her adulation of a fictional boy band, while her grandmother is essayed by long-time Aunor associate Gina Alajar, serving as the voice of caution regarding her own mother’s overwhelming, decades-spanning fanaticism.

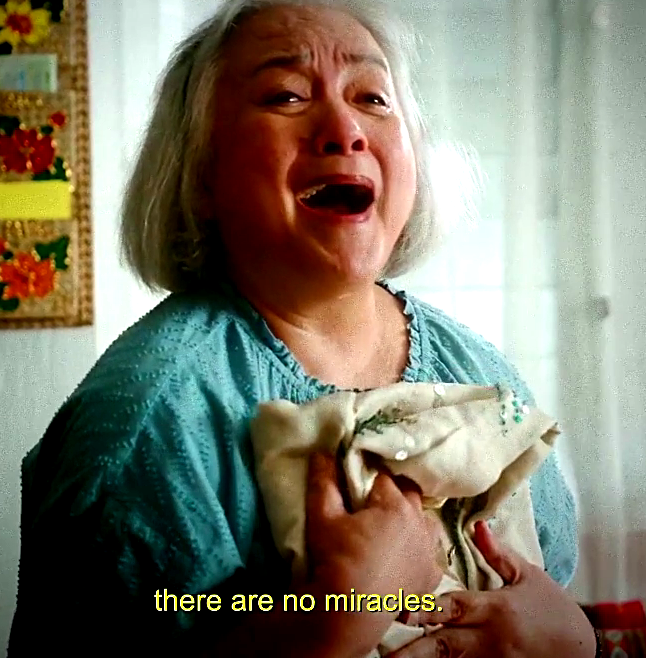

The great-grandmother on whom the narrative turns (described as “emotionally wrought yet effective” by film expert Jojo Devera) is embodied by Laurice Guillen, who springs a few surprises with her presence. She’d trained in theater, as Paulate also did, and where Aunor once immersed in productively: anyone fortunate enough to have seen this trio in their respective stage appearances would instantly understand why theater’s the actor’s true medium. But after several film directors, including the otherwise reliable Lino Brocka, could not maximize her performative potential, she found her own footing when she ventured into film directing. The first jaw-dropper is in how she never had any solo-lead film roles all this time, with Faney constituting only her second, after Jay Altarejos’s Guardia de Honor (2024). The more startling revelation is how perfect she turns out to be for the part, as if all the years of being kept from disclosing her full store of histrionic talent enabled an outpouring of, to use the proper descriptor, Noranian proportions.

Only favorable results can arise out of such an approach. The film’s few technical imperfections can be overridden by such an all-infusive display of prowess, with several introspective moments held fast by the eloquence of her appearance: where Aunor made her eyes speak volumes, Guillen deploys her entire face – an even more effective mechanism, truth be told. Her penultimate silent moment is when she encounters a male contemporary who we also see for the first time, and no words need to be uttered for us to deduce that he had shared a past with her. This also serves as a throwback to the climax of Aunor with Vilma Santos in Ishmael Bernal’s Ikaw Ay Akin (1978), which is not the only reflexive moment in the film. In fact the entire outing offers a cornucopia of references for any avid pop-culture follower, starting with the aliases the followers give themselves – “Bona” for Milagros (Guillen’s character) and “Pacita M.” for Paulate’s hell-raising smarty-pants – as well as wisecrack exchanges that sound increasingly familiar until the characters declare the titles of the source films.

But it’s the self-owned silent moments where Guillen makes her mark. The first one, when Milagros hears the news of Aunor’s death and brings out her memorabilia collection, sets the tone of melancholy over loss and aging with the comic undercurrent of insistent, undying obsession. The last one, where she stands with her family over Aunor’s grave and gazes in the distance, will reward any open-hearted viewer with an unexpected moment of grace that doesn’t have to be spoiled in a review. Just make sure to allow Faney to make the mark that Aunor left for us to savor.

.Joel David is a retired Professor of Cultural Studies at Inha University and was given the Art Nurturing Prize at the 2016 FACINE International Film Festival in San Francisco. He has written several books on Philippine cinema and maintains a blog at amauteurish.com.