Jason Reblando wanted to be a doctor like his parents. He worked in hospitals and conducted cancer research after graduating from Boston College with a bachelor’s degree in sociology. He applied to Loyola University Chicago’s medical school only to land on the dreaded waitlist.

He remembers calling Loyola’s registrar during the first week of classes from a pay phone at Wrigley Field. It was a bottom-of-the-ninth swing for the fences, but the result was a pop out. Loyola was full.

Reblando’s life was at a crossroads, but little did he know he had set his career in motion a few months earlier—whether by panic or prophecy—while signing his marriage license. Under the heading for occupation, he paused, thought, and scribbled an answer.

Photographer.

“Med school was still on the table, but that’s just what I wrote. I think I just wanted to make it,” Reblando said, laughing. “I don’t know if that was prophetic or what.”

Reblando wasn’t lying. He inherited an interest in photography from his mother, the unofficial family photographer, who gifted her son a Mick-A-Matic camera when he was 6 years old. He carried the interest through his formative years, vividly recalling a photo of the Jefferson Memorial taken on a class trip to Washington, D.C., being “ruined” by a wooden police barricade. It was the first time he cared what a photo looked like.

So, was he a photographer? Sure. But was it his occupation? Hardly.

“I only took one photo class as an undergraduate,” Reblando admitted. “I had a lot of fun in the darkroom, but I only did it as an enthusiast. I never thought it would be a vocation.”

With a career in medicine on hold, Reblando picked up freelance photography jobs in Chicago as his wife pursued a doctorate. He eventually enrolled in Columbia College’s M.F.A. program where he learned from his mentors and fellow graduate students how to think and create like an artist.

“That really changed everything,” Reblando said.

“I only took one photo class as an undergraduate. I had a lot of fun in the darkroom, but I only did it as an enthusiast. I never thought it would be a vocation.”

Jason Reblando

A hobby soon became a profession and, since then, Reblando’s photos have been published in The New York Times and collected in the Library of Congress. He’s earned grants and won awards. He’s shared his knowledge and enthusiasm for photography with the next generation through teaching and considers himself “blessed” to be a faculty member at Illinois State; he’s been an assistant professor of photography since 2020 and was previously an instructional assistant professor from 2012-18.

Passion projects have persisted through it all, as Reblando has pursued interests in planned communities and housing and social justice. His work has increasingly centered on the Philippines, the native country of his parents, who immigrated separately to the United States in the 1960s. (They met during their medical residencies at Fordham University.)

Reblando first visited the Philippines in 2005 with his parents and returned in 2015 on a Fulbright fellowship. His related works have focused either directly or indirectly on the country’s colonial past. The Philippines was governed by Spain from 1565 until 1898 when it was ceded to the United States as a result of the Spanish-American War. The islands were later occupied by Japan from 1942-45. The Philippines earned its independence at the conclusion of World War II, but lingering effects of colonialism remain.

On Reblando’s first visit to the country, he was struck by a fast-moving line at the airport he learned was designated for Overseas Filipino Workers (OFWs). It was then he became aware of the phenomenon of Filipino citizens working abroad in great numbers—the Philippine Statistics Authority measured the population at 2.2 million prior to the pandemic—many of whom sent earnings home to support their families. This realization led to Reblando’s 2015 series Home and Away, exhibited most recently last spring at the Illinois State Museum.

He went further back in history in his series Bataan Death March, which documented the modern-day places, people, and memorials along an 87-mile stretch Filipino and American soldiers trekked upon their surrender to the Japanese Imperial Army during the early stages of World War II.

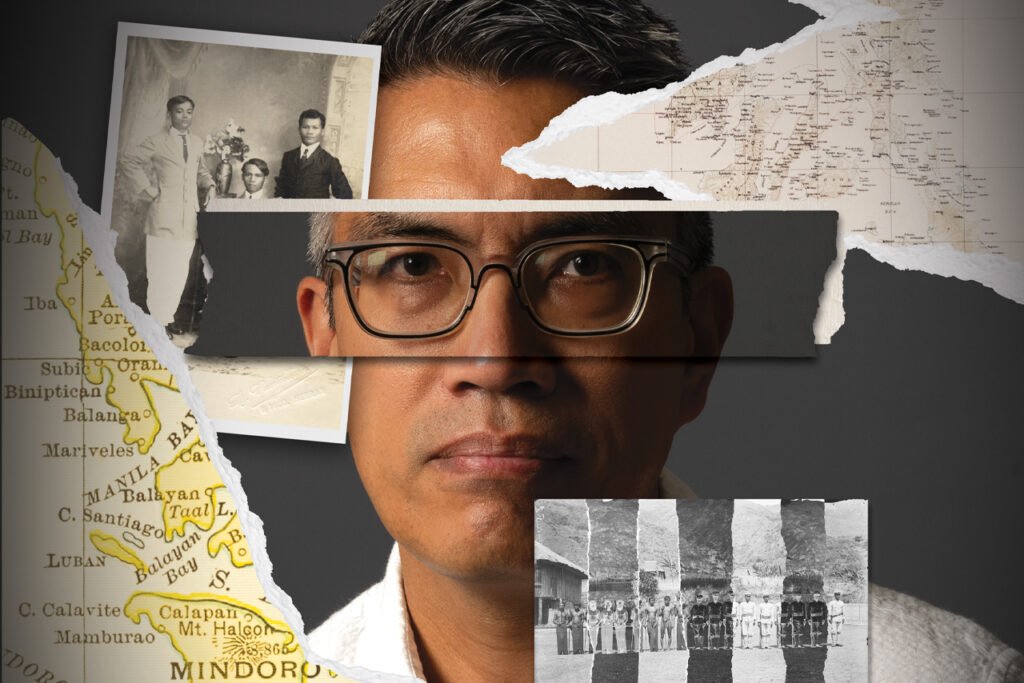

But his latest work is an altogether different project that’s equal parts research and creative expression. In This Is Captured Paper, Reblando features images procured from archives visited in person and accessed digitally in a mixed media presentation that utilizes collaging, splicing, and combining of images. Much of the source material came from the photographic archives of University of Michigan zoologist Dean Worcester, a controversial historical figure who first arrived in the Philippines on a scientific expedition but later became part of the American colonial administration in the early 20th century.

“I still consider myself a photographer, but I’m engaging with photography in just a completely different way now,” Reblando said.

The work represents the intersection of complicated history, modern perception, social justice, and the lived experience of his own family, including that of the parents who first nurtured his interest in photography.

“What’s funny is I keep going back (in time),” Reblando said. “It feels like there’s a through line because it’s all out of curiosity of my own family’s connection to the Philippines, but I think it’s all wrapped up together. You can go backward or forward to see how the Philippines was portrayed then versus how it’s viewed today, and I think all that matters.”

This Is Captured Paper was scheduled to be published this fall by the Los Angeles-based book studio For the Birds Trapped in Airports.

This Is Captured Paper

Jason Reblando selected and commented on pieces from This Is Captured Paper for Redbird Scholar. Comments are edited for brevity and clarity.

Ifugao Belle

“This is an image from 1895 of a young woman with a hand on her hip, naked from the waist up, and she’s draped with an ornate tapestry around her waist. My image includes a ruler and a color bar meant for cataloging, and my intervention here is collaging the image with diamond-shaped patterns, and it’s almost like you are looking through a kaleidoscope. My intent is to disrupt the colonial gaze, and I’m trying to hide images of nakedness or problematic images of colonization. It’s all very disorienting, and that was kind of my goal here.”

Mention the Geographic

“This is an image from the November 1913 issue of National Geographic credited to Dean Worcester. The original caption is ‘typical Kalinga couple,’ and I’ve collaged these star patterns cut from the cover of the National Geographic with its signature yellow border. It’s somewhat decorative but also a way of referring to Worcester’s hand in it. When I was in the archives, I noticed this tagline of ‘Mention the Geographic—It identifies you.’ It was on many advertisements, so if you walked into a travel agent, you identified yourself as a learned, middle- or upper-class person who was not only reading National Geographic but a person of the world. My take on that line is that National Geographic identifies you, the reader of National Geographic, but it also identifies, classifies, and objectifies whatever is viewed through its colonial lens.”

Dean C. Worcester and Wild Tingian Girl

“This is an illustration of Dean Worcester with a cutaway of his head showing another image from that issue of National Geographic, which has an original caption of ‘Wild Tingian Girl.’ The background is a postcard that’s titled ‘3,000 Manila schoolchildren doing calisthenics,’ and it’s a sea of children dressed in white being led through these exercises for fitness, for order, and it kind of feels like Worcester’s dream come true: Wildness giving way to order.”

Partially Civilized

“I saw this in the Peabody Museum at Harvard, an image of an American woman in a skirt and long sleeves standing next to a young Filipino boy dressed in a white suit with his feet bare and a straw hat in the corner. I came across it and was like, ‘Finally, a non-naked image!’ But I looked at the caption and it said, ‘Mrs. Jenks and a partially civilized Bontoc boy.’ And not only is it typewritten, but it’s written into the margins in penmanship. So, there’s a couple of generations of archiving here not only in ink, but in pencil, and for further research, it’s also written into the finding aid in the metadata. And when I saw this picture, it reminded me of my son. So, I cut out the boy and replaced him with a fern, which is an image I got from the University of Michigan Herbarium, because I wanted to shield and protect an innocent kid.”

Olympia

“Three-quarters of this image is taken up by the ship, the USS Olympia, which was commanded by Admiral George Dewey, who had defeated the Spanish fleet in the Battle of Manila Bay, and the ship is flying the American flag off the bow. The bottom part of the collage is a group of young women who comprise a baseball team, all in white uniforms, whose heads are cut off by the ship. I feel like it’s a commentary on the American project in the Philippines, the introduction of baseball, the introduction of this American ship in Manila Bay.”

Continental Drift

“This is a black-and-white image of a fleet of bancas. These are traditional Philippine boats almost like catamarans, and they’re all flying the American flag, and in the background, I’ve collaged or manufactured these little islands. While I was at the University of Michigan, I came across a library that specialized in maps, and I found a map of the United States and ‘its new possessions.’ And if you remember those AAA atlases that had that grid where you could match up your origin point with your destination to calculate the miles between them, that’s what you’re seeing here, with Manila sandwiched between Los Angeles and Milwaukee. And I thought that was interesting, like it really was part of the United States, just like Los Angeles or Milwaukee.”

National Geographic Bagobo Warriors

“This collage is made from an image from National Geographic of these Bagobo warrior headhunters Dean Worcester photographed. I’ve cut out the three men who had shields and stakes, and I replaced them with this bamboo tray that I grew up with that had a map of the Philippines on the belly of it. Most of the time it just hung on our wall, but the back of it had a list of phrases translating English to the Tagalog equivalent.”

Without Camisa

“This is a black and white image of a woman sitting on a riverbank, and it is blocked by the envelope that kept Dean Worcester’s glass plate negatives. This is from the University of Michigan, and as I was looking through the archive, there was a series of possibly two dozen images of this woman in various states of undress. In one, she’s breastfeeding her child. A couple later, she’s reclining bare breasted on a bed. A couple later completely naked reclining in this natural setting. This is all captured as part of Worcester’s ‘scientific work,’ and the caption on the envelope is written very clinically, but I need to think that this was all done under duress.”

This is Captured Paper

“This is from the University of California Riverside, and it’s from an execution chamber with a person using a garrote, which is a torture device. A person is strapped to the back a chair as the torturer screws a rod into the back of their neck to strangle or break the neck. So, I cut out the outlines of the person being tortured as well as the person turning the screw, and I replaced their bodies with a letter written by an American soldier recounting his experience in the Philippine-American War to his mother. There are comments about killing natives and finding the natives were better shots than what he expected. So, there’s a sense of surprise, a sense of condescension there. But the soldier also signed off with ‘P.S. This is captured paper,’ and when you inspect the stationary, it’s from the Philippine government, so it’s like a souvenir or a war trophy.”

Visit JasonReblando.com to see more of Jason Reblando’s work.