In a music scene where Western instrumentation still shapes much of what we hear on the radio and online, a number of Filipino artists have been carving out their own sonic paths by turning to the country’s indigenous roots. Whether it’s through kulintang gongs, bamboo zithers, or hybrid forms that mix field recordings with electronics, these musicians are building something personal, political, and deeply local out of it. For most of these artists, indigenous instrumentation is, in their hands, at the center of music making, moving beyond the conventional electric guitar, drum kit, and bass.

With Linggo ng Musikang Pilipino ending this month, we take a look at the long-running, multi-generational effort to keep cultural memory alive and how they’re made relevant by these modern day artists.

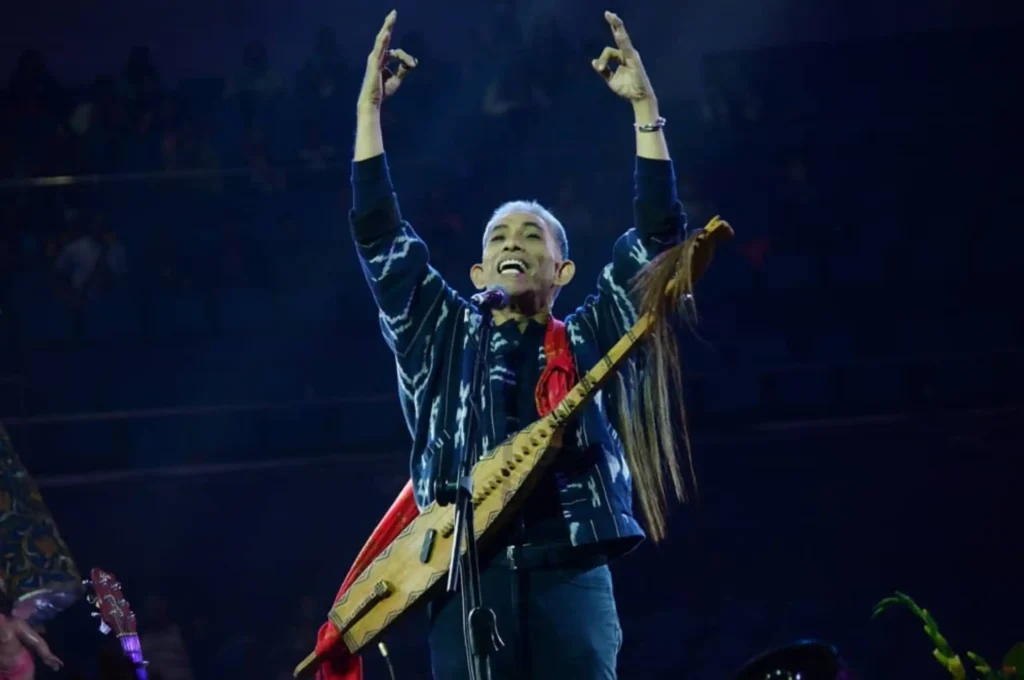

Joey Ayala has long been a key figure in the folk music space. Alongside his group Bagong Lumad, Ayala has spent decades incorporating instruments like the two-stringed lutes such as the hegalong and kudyapi into his songwriting. These choices are a statement of cultural presence and responsibility throughout his life’s work as a singer-songwriter, paying homage to traditional instruments from Mindanao. His songs speak plainly about land, displacement, language, and memory while allowing indigenous instruments to speak just as clearly.

Bayang Barrios, who first performed with Bagong Lumad, has grown into one of the strongest advocates for indigenous-centered OPM. As a Manobo artist, she folds ritual, resistance, and oral tradition into her music with conviction. Her songs combine indigenous rhythms and vocal techniques with sharp political presence in songs like “Biyaya” and “Bagong Umaga.” Her heritage is performed where music functions as witness and reminder, grounded in both community and lived experience.

Heber Bartolome’s work with Banyuhay in the 1970s merged folk rock with traditional instruments like the kubing and kulintang at a time when few artists attempted that kind of blend. Bartolome was responsible for pushing the modern day usage of indigenous instruments into public discourse. Songs like “Istambay” and “Nena” directly challenged colonial hangovers and framed Filipino identity without falling into easy nationalism with the use of the Filipino bandurria. His legacy cuts deep into the DNA of artists who refuse to flatten tradition to fit marketable categories.

Barbie Almalbis, known mostly for guitar-forward pop-rock, has explored indigenous instrumentation through select collaborations and live projects in Tower of Doom in 2022 and her Firewoman concert back in 2023. While not a defining part of her recorded catalog, these gestures show an artist who treats cultural forms with care. Rather than draping indigenous elements for flair, she threads them in with subtlety and respect with the use of the kudyapi, using them to expand — not exoticize — her arrangements.

Pantayo, the Toronto-based group of queer Filipina musicians, uses indigenous instruments like the kulintang, agung, and dabakan to build songs that live in the present tense, especially in their breakthrough self-titled sophomore album released back in 2020. Their music doesn’t frame these instruments as relics. Instead, they repurpose them alongside synths, basslines, and contemporary vocal styles, creating a soundscape rooted in memory but shaped by migration and reinvention. Pantayo’s body of work treats pre-colonial instruments to redefine the genre of pop through traditional means.

Alamat operates within the machinery of P-pop with the use of melodies, but doesn’t abandon cultural context from indigenous communities of the Philippines. The group foregrounds regional languages, indigenous motifs, and traditional percussive textures within the structure of Filipino boy band music in videos like “Maharani” and “Dagundong.” Their visuals draw from pre-colonial aesthetics without animating or appropriating for visuals sake, and one of her producers like Nick Lazaro have consistently worked with melodic frameworks drawn from folk forms. From the very start, Alamat’s intent is to hold up as cultural assertion within an industry that rarely demands it.